Prior to the Bolshevik revolution, there were hardly any Russians who emigrated to the United States for non-religious reasons, Ivan Turchaninov is one of those few.

Prior to the Bolshevik revolution, there were hardly any Russians who emigrated to the United States for non-religious reasons, Ivan Turchaninov is one of those few.

Ivan Turchaninov, or John Basil Turchin as he called himself in America, was the only the Russian-American general in the United States Civil War. Born into a Don Cossack family on December 24, 1821 in Russia, Ivan had possessed a bright military career as early as the age of 11 when he was sent to learn at Novocherkassk, the capital of the Don Cossack region. Three years later he entered the Mikhailovskiy Artillery School in St. Petersburg, which trained Turchaninov for five years on aspects of math and engineering. Upon graduating in 1841, Turchaninov was assigned to an artillery unit in Poland. Finally, at the age of 30, he enrolled in the Imperial Military School in St. Petersburg, later becoming chief of staff among the Russian Guards and fighting in the Crimean War and Hungary.

In May of 1856, he married the daughter of his commanding officer, Nadezhda Lovov, and immigrated to the United States. Anglicizing their names to John and Nadine Turchin, the couple settled on a farm on Long Island, New York. Losing the farm a year later due to an economic downturn, the couple moved to Philadelphia where John attended engineering school.

While the exact reason for the Turchin’s immigration to America is never quite known, it might have been the fact John’s political views, which would be considered liberal by Russian standards, were not encouraged, as evidenced by the failure of the Decembrist uprising. But despite moving to the land of the free, the couple’s first years in America were none too pleasant as they had experienced a number of failed ventures, in one letter John writes:

While the exact reason for the Turchin’s immigration to America is never quite known, it might have been the fact John’s political views, which would be considered liberal by Russian standards, were not encouraged, as evidenced by the failure of the Decembrist uprising. But despite moving to the land of the free, the couple’s first years in America were none too pleasant as they had experienced a number of failed ventures, in one letter John writes:

“I thank America for one thing, it helped me get rid of my aristocratic prejudices, and it reduced me to the rank of a mere mortal. I have been reborn. I fear no work; no sphere of business scares me away, and no social position will put me down; it makes no difference whether I plow and cart manure or sit in a richly decorated room and discuss astronomy with the great scholars of the New World. I want to earn the right to call myself a citizen of the United States of America”

After finishing Engineering school, John and Nadine moved a second time to Chicago, Illinois where Nadine would work in medicine and John would work for the Illinois Central Railroad as an assistant to the company’s vice president and chief engineer George McClellan (who Turchin had met during his service in the Crimean War) until 1861, where his skills with the Russian Imperial Army found him a place as a colonel among the ranks of the Union army.

On June 17, 1861, the 19th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry marched into the south, with John Turchin in command. Soon after, the regiment was under command of the Army of the Ohio. Impressed by Turchin’s skills as a leader, Don Carlo Buell (who was leader of the Army of the Ohio at the time), gave a promotion and command of a brigade from the army’s Third Division, originally only under the command of Ormsby M. Mitchel.

On June 17, 1861, the 19th Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry marched into the south, with John Turchin in command. Soon after, the regiment was under command of the Army of the Ohio. Impressed by Turchin’s skills as a leader, Don Carlo Buell (who was leader of the Army of the Ohio at the time), gave a promotion and command of a brigade from the army’s Third Division, originally only under the command of Ormsby M. Mitchel.

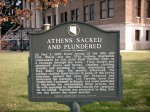

With orders to hold Nashville, Turchin convinced Mitchel to head south, which would eventually lead to the taking of Huntsville, Alabama and severed the rail communications of the Confederacy from east to west. But this victory did not last long and troops were attacked by Confederate troops, eventually leading to a temporary retreat by the Union. One of the most notable instances of this was in nearby Athens, a small town of a population made up of roughly 900 people, where several of Turchin’s regiments had become so agitated they began to harbor antagonism against the people of the city. Turchin, after learning that the civilians of Huntsville had prevented several blacks from rescuing a Union soldier from being roasted alive between the engine and coal-car of a destroyed train, had become enraged himself, this is when he allowed his troops to pillage the town after reinforcements had arrived, this would become known as the Rape of Athens.

Despite Buell’s wish to protect the property and rights of the southerners, after receiving confirmation the Confederate presence in the area was indeed eliminated and that there would be threat of enemy retaliation, Turchin gathered the regiment and told them “I close my eyes for two hours. I see nothing”, just before leaving the town for a meadow where he would stay for the rest of the day. The regiment went on a rampage, ransacking businesses and stealing or destroying merchandise, one report mentions a stock of books, with bibles and testaments among them, were ripped apart and kicked about the floor while another mentions a jewelry store was broken into, with soldiers stuffing their pockets with as much valuables as they could steal. Soon, homes and living areas were also raided, one pregnant woman was so terrified she suffered a miscarriage and later died herself.

Despite Buell’s wish to protect the property and rights of the southerners, after receiving confirmation the Confederate presence in the area was indeed eliminated and that there would be threat of enemy retaliation, Turchin gathered the regiment and told them “I close my eyes for two hours. I see nothing”, just before leaving the town for a meadow where he would stay for the rest of the day. The regiment went on a rampage, ransacking businesses and stealing or destroying merchandise, one report mentions a stock of books, with bibles and testaments among them, were ripped apart and kicked about the floor while another mentions a jewelry store was broken into, with soldiers stuffing their pockets with as much valuables as they could steal. Soon, homes and living areas were also raided, one pregnant woman was so terrified she suffered a miscarriage and later died herself.

The townspeople estimated the damages of the rioting to be at least $55,000. Facing court martial, Turchin was on trial before Brigadier General James A. Garfield, who would later become a president of the United States. At the trial, Turchin argued that his superiors had been treating the rebels too softly, arguing that “the more lenient we become to secessionists the bolder they become”. While this did win Garfield and many others to his side, Turchin was still found guilty “of conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline.”

The townspeople estimated the damages of the rioting to be at least $55,000. Facing court martial, Turchin was on trial before Brigadier General James A. Garfield, who would later become a president of the United States. At the trial, Turchin argued that his superiors had been treating the rebels too softly, arguing that “the more lenient we become to secessionists the bolder they become”. While this did win Garfield and many others to his side, Turchin was still found guilty “of conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline.”

Turchin’s wife, Nadine Turchin met with President Lincoln to plead her case, stating that John’s nomination for promotion to brigadier general should waive his punishment, which after a vote in the Senate of twenty to eighteen, did just that, much to the dismay of Don Carlo Buell, who sought punishment for Turchin. Following this, Turchin returned to service as a general officer.

Turchin’s wife, Nadine Turchin met with President Lincoln to plead her case, stating that John’s nomination for promotion to brigadier general should waive his punishment, which after a vote in the Senate of twenty to eighteen, did just that, much to the dismay of Don Carlo Buell, who sought punishment for Turchin. Following this, Turchin returned to service as a general officer.

Returning to Chicago, John Turchin received a hero’s welcome and now had more supporters behind him than ever, some even saying the aggressive policies with Athens should be applied to the war as a whole and others calling for the demotion of Buell. In fact, the Chicago Tribune praised Turchin, stating that he “has had, from the beginning, the wisest and clearest ideas of any man in the field about the way in which the war should be conducted.” and that he is one “who comprehends the malignant character of the rebellion and who is ready and willing to use all means at his command to put it down.” after sponsoring his promotion to General at Chicago’s Bryan Hall.

Following this, Turchin continued his military command at the battles of Chickamauga, Chattanooga and Atlanta (Interesting fact, another Russian, Aleksei Smirnov, was in Turchin’s regiment during the battle of Chickamauga, dying in battle). During this time, Nadine Turchin, or Madame Turchin as she was known to many, followed John Turchin’s campaigns and witnessing the battles her husband had taken part in, writing her experiences in a diary, the manuscript of which is now in the hands of the Illinois Historical Society. Remarkably, Nadine Turchin was the only Union woman to have written a diary on her experiences during those battles.

Following this, Turchin continued his military command at the battles of Chickamauga, Chattanooga and Atlanta (Interesting fact, another Russian, Aleksei Smirnov, was in Turchin’s regiment during the battle of Chickamauga, dying in battle). During this time, Nadine Turchin, or Madame Turchin as she was known to many, followed John Turchin’s campaigns and witnessing the battles her husband had taken part in, writing her experiences in a diary, the manuscript of which is now in the hands of the Illinois Historical Society. Remarkably, Nadine Turchin was the only Union woman to have written a diary on her experiences during those battles.

Shortly after the end of the Atlanta Campaign in September of 1864, Turchin suffered heatstroke and as a result resigned from service. For the remainder of his life, John Turchin worked a number of jobs including patent solicitor, civil engineer and eventually real estate, where he would help find land for immigrants like him in southern Illinois. He could hardly make ends meet, seeing this, his old comrades-in-arms appealed to congress to grant Turchin a payment of fifty dollars per month as pension, despite this, John and his wife were still quite poor.

Turchin died on June 18, 1901 at the age of 79, in an institute as a result of his heatstroke-attributed dementia. Although Ivan Turchaninov’s role in the Civil War was small, because of his actions at Athens, he garnered nationwide attention and brought up the question of military conduct in a civilian area among the American people.

Turchin died on June 18, 1901 at the age of 79, in an institute as a result of his heatstroke-attributed dementia. Although Ivan Turchaninov’s role in the Civil War was small, because of his actions at Athens, he garnered nationwide attention and brought up the question of military conduct in a civilian area among the American people.

Known as “The Mad Cossack” and “The Russian Lightning Bolt”, Many remembered him for the way he would shout orders in a thick accent, quickly becoming popular for this among the Union soldiers, a song was even written parodying the Confederate song “Here’s Your Mule”, titled “Turchin’s got your mule”, recounting how his regiment seized Southern property and livestock at Alabama. The the lyrics of the song are as follows:

“A planter came to camp one day,

His niggers for to find,

His Mules had also gone astray,

And stock of every kind.

The planter tried to get them back,

And thus was made a fool,

For every one he met in camp

Cried “Mister here’s your Mule.”

Chorus — Go back, go back, go back, old scamp,

And don’t be made a fool,

Your niggers they are all in camp

And Turchin’s got your Mule.

His corn and horses all were gone

Within a day or two,

Again he went to Col. Long,

To see what he could do.

I cannot change what I have done,

I wont be made a fool,

Was all the answer he could get,

The owner of the mule.

And thus from place to place we go,

The song is e’er the same,

T’is not as once it used to be,

For Morgan’s lost his name.

He went up North and there he stays,

With stricken face, the fool ;

In Cincinnati now he cries,

“My Kingdom for a Mule.”

And so ends the tale of Ivan Turchaninov, the man who began a legacy of Russian life in America and the man who defined the Russian-American view of the United States as stated by one of his comrades-in-arms, “He was one of the best-educated and knowledgeable soldiers of the United States. He loved this country more than many American-born citizens did”.

Read more on Turchaninov at these links:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Turchaninov

http://civilwar.bluegrass.net/battles-campaigns/1862/620502.html

http://www.lib.niu.edu/1997/iht429748.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athens,_Alabama

http://02varvara.wordpress.com/2008/02/12/ivan-turchaninov-a-russian-general-in-the-union-army/

http://www.peoples.ru/military/colonel/ivan_turchaninov/

http://www.suite101.com/content/nadine-turchin-fights–beside-her-husband-john–in-the-civil-war-a257025

http://www.jstor.org/pss/40191694

http://www.chattanoogacwrt.org/200803.htm

http://english.ruvr.ru/2007/03/09/125029.html

http://encyclopediaofalabama.org/face/Article.jsp?id=h-1652

http://d-pankratov.livejournal.com/663214.html

Shared this on Facebook or myspace. I obtain this web-site definitely . I figured out a great deal from this. Content wise, it honestly is amazing.

after learning that the civilians of Huntsville had prevented several blacks from rescuing a Union soldier from being roasted alive between the engine and coal-car of a destroyed train, had become enraged himself, this is when he allowed his troops to pillage the town after reinforcements had arrived, this would become known as the Rape of Athens.

Do you have a citation for the story about the Union soldier.